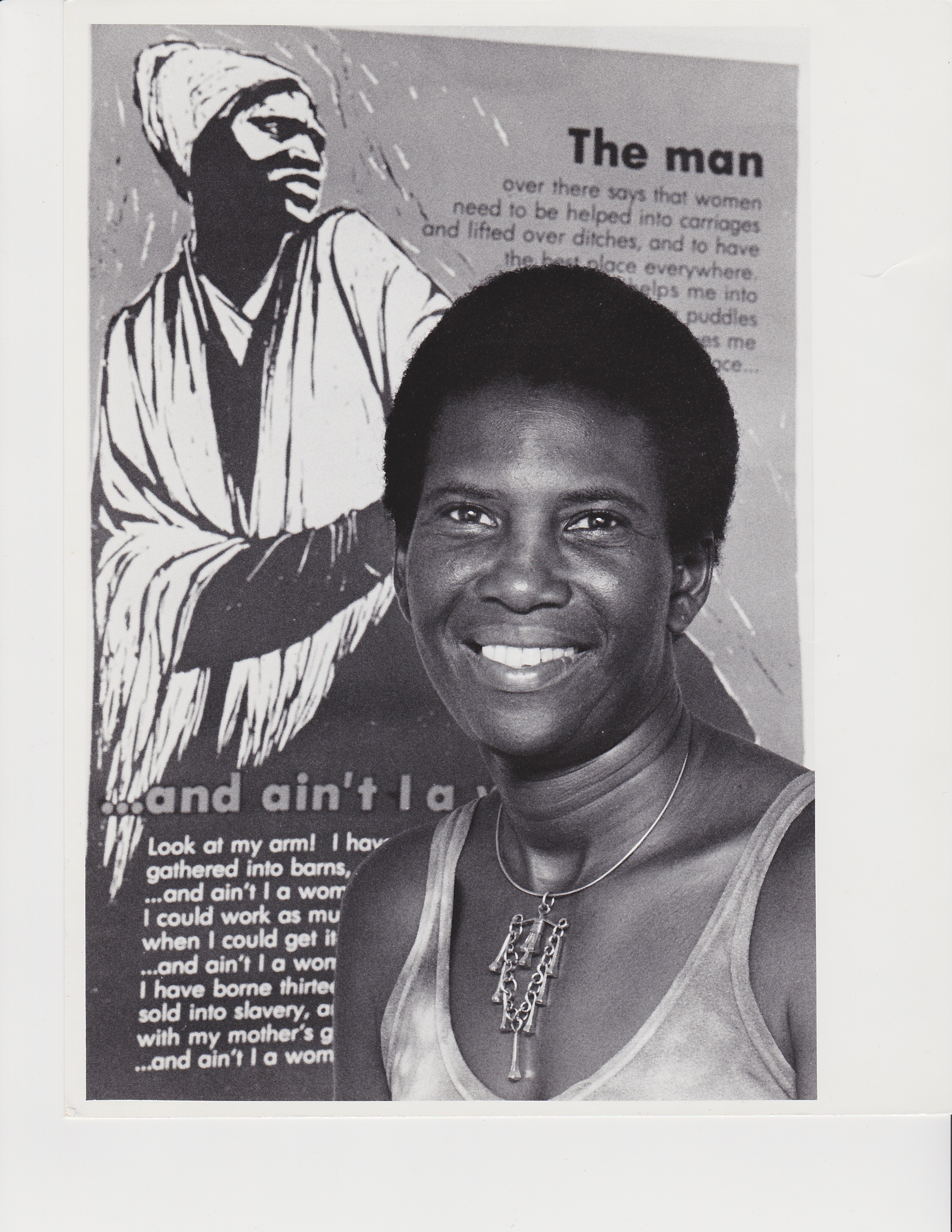

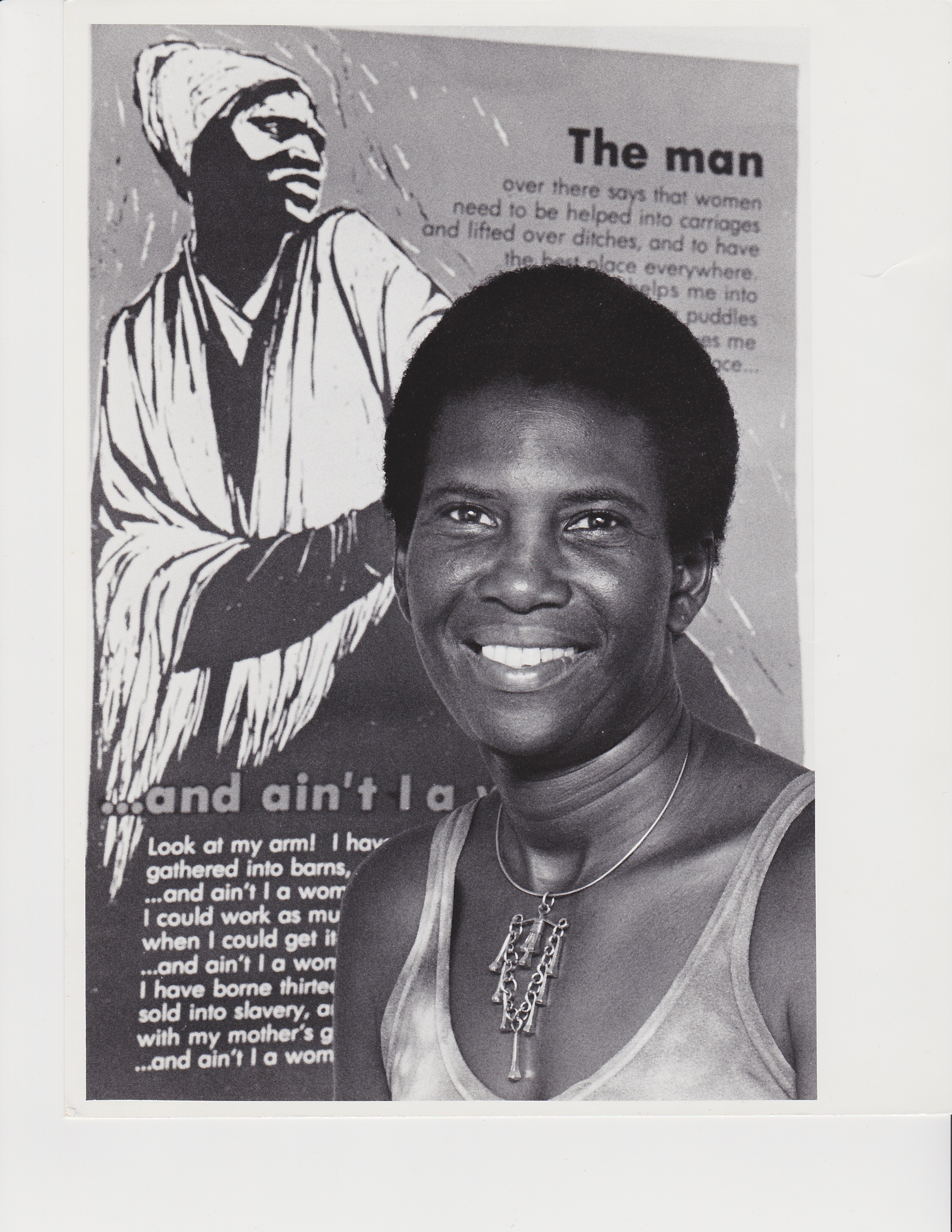

Avery, Byllye

Rose Norman interviewed Byllye Avery by phone in February 2013.

Biographical Information

Byllye Yvonne Reddick Avery (b. 1937) was born in Waynesville, GA, and her family moved almost immediately to DeLand, FL, where she was raised. She graduated from Talladega College (a prestigious HBCU in Alabama) in 1959, married in 1960, and had two children (Wesley and Sonja). In 1970, her husband, Wesley Avery, died suddenly of a massive heart attack, while they were both in graduate school at the University of Florida. Wesley Avery’s death radicalized her, and she has been an activist around Black health issues ever since. In the 1970s, she served on the Board of Directors of the National Women’s Health Network and in that capacity connected to the Boston Women's Health Collective that published the first Our Bodies, Ourselves (1971). One of her earliest health advocacy actions she co-founded the Gainesville Women’s Health Center (with Judy Levy and Margaret Parrish), and in 1978 BirthPlace, also in Gainesville. This work in Gainesville raised her awareness of the need for better counseling and education around Black women’s health issues.

After moving from Gainesville to Atlanta, she founded the National Black Women’s Health Project (1983), now known as the Black Women’s Health Imperative (healthyblackwomen.org). Since that time, she has received many major honors, including (and this is not a complete list) the MacArthur Foundation Fellowship for Social Contribution (usually known as “genius grants”) and the Essence Award for Community Service (both in 1989), the Dorothy I. Height Lifetime Achievement Award and the President's Citation of the American Public Health Association (both in 1995), the Ruth Bader Ginsberg Impact Award from the Chicago Foundation for Women (2008), and the Audre Lorde Spirit of Fire Award from the Fenway Health Center in Boston (2010). She is the author of An Altar of Words: Wisdom to Comfort and Inspire African-American Women (1998). Today she lives in Provincetown, MA, with her partner of 26 years Ngina Lythcott, whom she married in 2005.

In 2005, Byllye Avery did an intensive interview for Smith College’s Voices of Feminism Oral History Project. (Byllye Avery interview by Loretta Ross, video recording, July 21, 2005, Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection, 5 60-minute tapes. Online transcript, www.smith.edu/libraries/libs/ssc/vof/transcripts/Avery.pdf ) The 95-page transcript of that interview is available online, and covers her entire life, with much detail about her work with women’s health advocacy (www.smith.edu/libraries/libs/ssc/vof/transcripts/Avery.pdf). Rather than replicate that interview, we developed questions that build on it.

On feminist activism

It is unusual (among feminist memoirs) that you were radicalized by your husband's sudden death, and not by some sexist event. How did your interest in health issues after Wesley Avery's death get translated into a feminist approach to Black women's health issues?

"When my husband died, I became very aware of how vulnerable we all are, even at a young age. He was 33 years old. I became really aware of how important it is to have information about your health. We did not have any health information at that time that could have prevented his death. This was before the campaign about high blood pressure being the silent killer. He had had a physical in which his blood pressure was high, and they laid him down for 20 minutes and took it again and it was normal. That was 10 years before, when he was about 23 years old. That happened a couple of times. But we were never told about the dangers of untreated high blood pressure."

"That all happened to me when I was working at Shands Teaching Hospital [in Gainesville] at the Children's Mental Health Unit. We were looking at new ways of looking at health, health messages, and educating the public. People were only beginning to ask questions about their bodies. So along comes the women’s movement, which questioned everything, and the women’s health movement, which kept that going, based on the same premise, that we have a right to know and own our bodies and know about our lives. When I started with the women’s health movement, we were doing everything, from teaching vaginal self-exams, to breast exams, to reading Our Bodies, Ourselves. That’s the piece that worked for me, the lack of information as it related to our health and then putting a feminist analogy around it."

What pushed you in the direction of feminism? Was it people at the Children's Mental Health Center?

"The women’s movement was happening all around us. You’d have to be a stone not to be aware of it, or an anti-feminist. I wouldn't say anybody pushed me into it. I ran willingly. It was new, it was fresh, it was exciting, exhilarating, empowering, it was a philosophy that I felt I could live my life by, my entire life. One of the last books that Wesley read was The Feminine Mystique, and he kept telling me he thought I should read that book, that I would really like it. So when I finally read it, I thought, oh my God, here it is! I wished I’d had the chance to have that conversation with him."

On working with white women and being a lesbian

In the Smith interview, you mention that going to UF (in 1968) was the first time you had worked mostly with white women, and that the campus had only about 30 Black people at that time. Later you say that white women were more accepting of you as a lesbian, but that your sexual orientation didn't matter with the Black Women's Health Project.

"I found a lot of acceptance among white women. My exposure to working and being around white people was at the University of Florida. I received a fellowship to attend UF and all of my classmates were young white women, and we kind of all hung together, three or four of us, and it was really pleasant and it was a sort of gentle way of learning about white culture. My husband told me “please go down there and find out how white people can go to school and be married.” We didn't know about things like that you could get university housing that cost $70 a month and came fully furnished. It was a whole cultural education being at the University of Florida. And through the Gainesville Women’s Health Center, Margaret, Judy, and I became real close."

"Coming out as lesbian was an interesting process, to say the least. I felt a lot of acceptance. I never felt that the Black women rejected me so much as they didn't know what to do with me. By the time I got to the Black Women’s Health Project there were several women on the planning committee who were lesbian, and one of the things we worked on was homophobia."

On feminism and ethnicity

In the Smith interview, you say "Black women are more feminist than white women," [p 52; tape 3] citing a poll. I'd love to hear you say more about that, especially in light of what Pam Smith had to say about Deborah David thinking the GWHC should focus more on Black women's health, and that white women didn't really need women's liberation.

"You have to think about perspective and women’s position. What the women’s movement was espousing was that white women who were at home, bored, were wanting to get into the workforce, and a lot of them were well off financially and had what Black women thought was independence, because they [Black women] were certainly tied down further than that. So of course Black women wouldn't think white women needed it. It was just a matter of perspective and point of view, where people sit in society and how they view what’s happening. Whether it’s true or not has nothing to do with it. What Black women couldn't see was how white women were feeling about their lives. Most Black women experiencing degrading behavior and low pay, would have liked to have the luxury of staying at home and having someone take care of them. Working in their homes as maids, they saw them going off and having tea and acting like they were having fun. People didn't talk with each other about what their inner feelings were. But remember this was a new awareness time, and people hadn't shared things in ways that we are sharing now."

"What I meant by Black women being feminist was that, in terms of having a womanist approach to life, before I heard the word feminism, I grew up being able to depend on myself, to count on myself, knowing that women needed to be educated, to know how to do everything. It didn't so much come from a feminist base, but a base around racism, because the culture treated Black men so poorly until Black women knew we had to be responsible for taking care of our families. The Black men in the past had been incarcerated, a lot of time unjustly, and now they’re part of the prison industrial complex. That’s what I meant, that it really was more women taking the lead, women being strong, being independent. Of course, feminism is much more than that, but people take the slice that works for them at the moment."

So let me say this back to you and make sure I understand your meaning. The feelings of self-reliance and independence and personal responsibility that the women’s movement brought to white women were already there in Black women?

"Yes, and you have to look at the situation for Black men. There were limited jobs for them. A lot didn't finish school. So you had Black women like my mother, who was a teacher and had a master’s degree, and neither of the men she married even finished high school. Very seldom did you find teachers marrying doctors. Most of the women had the education. The Black community really stressed on the girls getting an education rather than the boys."

I’m still trying to figure out what happened with Deborah David.

"She thought white women had everything. You’re free, white, and you’re 21. So what do you need to be liberated? You got money, a house, a man taking care of you. That’s liberation. That’s what she took away from feminism. It’s your point of view. White women are wanting to go to work, and Black women have been working all the time and would like to be at home. She didn’t know the other side of it, that white women were unhappy, hadn't made advances, had college degrees and had to act like buffoons. We were just coming out of being integrated at all, less than ten years. It was the early 70s. Deborah was also a cultural nationalist, which is another slice, racist ideology on top of feminist ideology."

So was the GWHC serving many Black women?

"Yes, about 50% of clients who came in for abortions were Black, but not very many Black women used the well woman/GYN clinic. And that’s why I wanted to find out more Black women’s health and what were we doing, and how our lives were being shaped."

On the GWHC, BirthPlace, and Black Women’s Health Project

In the Smith interview, you say that your later work on broader health issues--like health care reform, lobbying for single payer, dealing with BC/BS-- is important but doesn't feed your soul the way the Black Women’s Health Project did (p 53), and before that the Gainesville Women’s Health Center. Can you talk about that?

"The Gainesville Women’s Health Center and BirthPlace both fed my soul. At the Gainesville Women’s Health Center we did a lot of education with women about their bodies, a lot of workshops and consciousness raising groups— a lot of things to help us understand who we are. I noticed that Black women were not participating in that, and I couldn't understand why. I was there, and we tried to make Black women comfortable, but they were just very, very uncomfortable."

"Now Birth Place, the power of birth, was one of the best experiences I’ve had in my life. It was totally awesome, just incredible learning and excitement, and understanding the spirituality around birth, and the importance of educating entire families around the whole experience of birth. It was very enlightening and exhilarating, an incredible experience there at Birth Place. I wrote about it in “Bearing Witness to Birth” in Women’s Quarterly. [Footnote: Women’s Quarterly vol 34 no 1&2 summer/spring 2008]

"At Birth Place I also learned the importance of education around health care procedures. My whole transition from the birthing center to the Black Women’s Health Project was interesting. I started working as a director for a CETA program at Santa Fe Community College in Gainesville and started looking at the lives of these young Black women registered in the program. Because I was the director, I learned when they were out, absenteeism, and I would bring them in to talk to them about why they couldn't come to class. They were getting minimum wage to come to class, and when they didn't come they didn't get paid, so I knew there had to be something that was keeping them from coming. I found out that a lot of them were ill, or had children who were sick, who needed to be taken care of. They just had all kinds of responsibilities. I realized that working women with children need 10 sick days for every child, and 10 days for themselves—but you only get 10 sick days. They just had so many circumstances I had never thought about, including poor health."

"It was then that I knew I really had to do something about bringing Black women together to look at health issues. I tried to do it in Gainesville, and I couldn't get the local Black women involved They were kind of suspicious of me. It wasn't that they didn't like me—they didn't understand me. Here I was involved with abortion, and at the birthing center with these white women. They were never disrespectful to me, but we were very uncomfortable with each other because they couldn't understand what I was into."

"That’s why I moved from Gainesville to Atlanta. When I moved to Atlanta, it was magical. Every door I touched opened. Every person sent me to see 3 or 4 more people who were helpful, and it was quite an extraordinary experience. We organized the first national conference on Black women’s health issues. We met for two years at Spelman College and organized. It was really quite wonderful. Everything just fell into place. It was a thing that was supposed to happen there. The response from the women was incredible. Atlanta’s a talkative town. This person would send me to another person, and I was amazed that all the people I was talking to in positions of power were Black, and were all willing to help, and were all on board with what I was talking about."

"We planned for two years for the first conference in June of 1983. We thought we’d have 200-300 women come. We had close to 2000, and they came from all over, including Canada and the Bahamas. We had buses rolling in there. Women would pay $25 in New York City and ride a bus all the way to Atlanta. After that, we started organizing Black women all over the country. They would have these Black women’s health conferences. We did a film called On Becoming a Woman: Mothers and Daughters Talking Together, about menstruation, and about our feelings. I believe that’s still in circulation. For the last thirty years, we’ve been pounding away."

Did you meet Black lesbians through BWHP?

"It was through the Black Women’s Health project that I began to meet Black women, generally. I got to meet people from all over the world— Brazil, Africa, the Caribbean, you name it. We went everywhere. We raised the money through foundations to work with those groups around the world. BWHP was a 501c3, and had an international division."

What kind of budget did you have?

"We got our first million dollars about 5 years into it. Kellogg gave us our first million dollar grant, spread over 2-3 years. We used these funds to work with people in various places, doing women’s conferences. We took delegations to the UN Conferences on Women—we took 25 women to Africa for the conference in Nairobi, Kenya. Close to 2000 Black women were at that conference in Kenya. We also went to the one in Beijing."

Is the mission of the Black Women’s Health Imperative the same today as when you began?

"Absolutely, but our strategy is different. When we started out we did a lot of work around personal empowerment, but now we work on community empowerment and working with communities to help make health changes. In the personal empowerment phase, we organized self-help groups that ran 10-15 years. In that way, we could look at what were our main issues. One of the first things we talked about was violence. Violence was our number 1 health issue. We identified that in about 1984-85. Later on we had places like the CDC talking about it, but we were the first to identify violence as a health issue. We weren't able to continue to raise money for the self-help part of the program. We weren't smart enough to have made them self-supporting from the beginning. I wish we had."

"So we moved to Washington, DC, in 1992, and switched over to working on public policy and working with communities to make health changes. We recently got funded to do work around diabetes education, a four-year $4 million grant from the CDC. We’re working on reproductive justice, and we’re still working on abortion rights, how can we change the conversation around Rowe. Instead of just saying that Black women have more abortions than others, we look at what are those circumstances, and the conspiracy of silence around it. We’re starting to look at Black maternal health, too. Black women are dying disproportionately within the first year after having a baby. We want to bring attention to that. We’re working on health reform. That’s the work I started with the Avery Institute for Social Change." [FOOTNOTE: a transitional organization between starting the National Black Women’s Health Project and then returning to it in when it became the Black Women’s Health Imperative.]

Can you say more about what it is that feeds your soul about this work?

"What fed my soul was watching women grow. Watching people feel good about themselves, watching people fall in love with themselves, develop strategies that help them survive, and give them a philosophy, a way of thinking and being, that could be shared with their families. The fact that the women had the courage to break the conspiracy of silence about physical abuse, about sexual abuse—which we found was rampant—about all of these things that we kept inside of us and felt bad about, that we learned how to turn that around, how to look at our fears and gain strength from our fears rather than letting our fears continue to disempower us. Watching people grow and change and take charge of their lives was just totally awesome. Just being in the company of women, all talking and being loving and caring toward each other, I find very wonderful."

"Empowerment comes from ideas."

― Charlene Carruthers

"Your silence will not protect you."

— Tourmaline

"Gender is the poetry each of us makes out of the language we are taught."

— Leila Raven