Review of In Thrall by Jane DeLynn

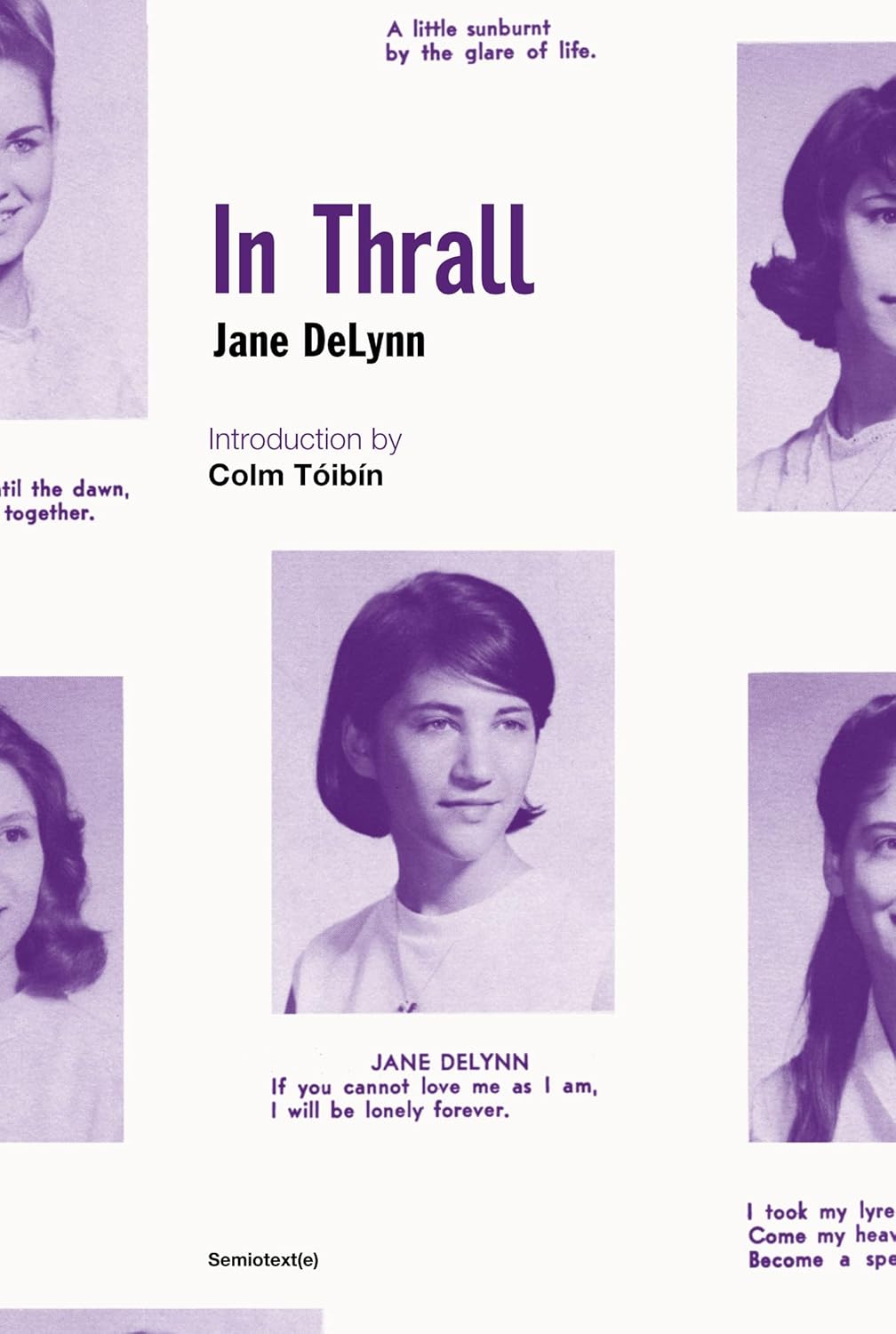

In Thrall

Jane DeLynn

Semiotext(e), 2024, 272 pages

$17.95

Reviewed by Lindsey Blaser

“Of course not, my dear, every quiver of your feverish sensibility holds me in thrall (143).”

Jane DeLynn’s In Thrall is a delicious read charting the affair between a budding lesbain and her English teacher in 1960s New York. While the inappropriate dynamic of the pair’s relationship is the hook, it’s far from the purpose of this novel.

Our hopelessly tragic protagonist, Lynn, is a timeless representation of many queer women’s experiences. Dismaying moments of forgetting to breathe, not being able to eat her Milky Way breakfasts anymore, and inexplicably being drawn to someone no one else understands—are niche experiences that broadly hold familiarity for the vast majority of queer youth.

The novel avoids delving into the intricacies of the couple’s relationship, especially their sexual encounters, and focuses instead on transferrable moments of Lynn’s queer adolescence. Lynn speaks only of unsavory experiences with her clumsy boyfriend, Wolf, so that all we read is of jamming fingers and coercion. When Lynn and Miss Maxfield enter the bedroom, it feels like a curtain closes, and the reader is left with a privacy which feels respectful, non-sexualized, and tender.

Miss Maxfield, having multiple student affairs in the past, is most objectively a predator. But it doesn’t feel that way as you read it. DeLynn wrote a novel in which bits of their interactions feel special and Miss Maxfield seems nurturing, which is conflicting as a reader. One is left to wrestle with the question of whether or not any part of their relationship is endorsable. And of course, it isn’t. Why the women are even attracted to one another is a mystery, feeling underdeveloped and vague, as if some otherworldly force is drawing the two together. What is it Lynn even likes about her? What do we, as readers, even like about Lynn?

Quippy remarks with her friends, an unbreachable wall up with her parents, and new vocabulary flaunted as soon as she learns it, are features that make Lynn relatable. The reader regresses to feeling like a teenage girl, especially one unraveling her sexuality. Lynn jumps to tragic extremes, finds her boyfriend disgusting (yet keeps him on the side), and panics when she reads fear-mongering homophobic texts. Basking in a tragic hero state, she believes a life of loneliness, crew cuts, and wearing green on Mondays is all that awaits her as lesbian. It’s almost healing to read this in 2025 and say, “My dear. . . ” alongside Miss Maxfield. How good things will become for us all!

Therein lies the draw to Miss Maxfield, someone who can offer assurance that Lynn’s identity isn’t life-ruining. She is someone who we, as twenty-first-century readers, view as a lifeline, while Lynn toys with the idea of throwing herself off a roof. Miss Maxfield is a voice of queer reason, giving Lynn grounds to believe it is more than okay to be gay. I just wish she was 16, too.

Lindsey Blaser holds a bachelor’s degree in Critical Diversity Studies from the University of San Francisco, and is a Sinister Wisdom intern based in New Jersey.

"Empowerment comes from ideas."

― Charlene Carruthers

"Your silence will not protect you."

— Tourmaline

"Gender is the poetry each of us makes out of the language we are taught."

— Leila Raven