Review of My Withered Legs and Other Essays by Sandra Gail Lambert

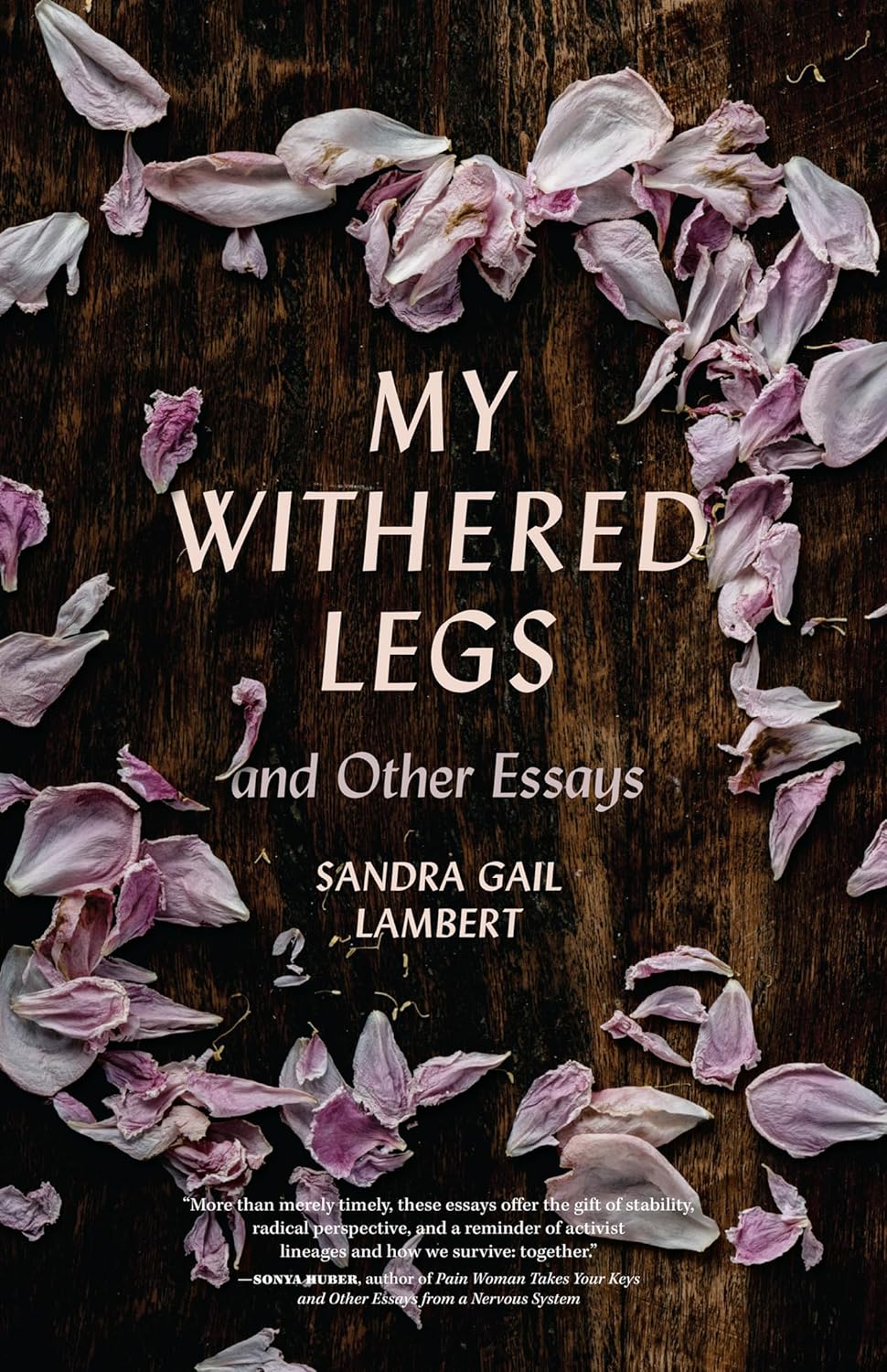

My Withered Legs and Other Essays

Sandra Gail Lambert

University of Georgia Press, 2024, 152 pages

$23.95

Reviewed by Kali Herbst Minino and Gabe Tejada

My Withered Legs is Sandra Gail Lambert’s new memoir essay collection observing shifting relations between the different facets of her life–including writing, disability, aging, and autonomy.

Throughout, Lambert conceives of and interrogates power through a spectrum of in/dependence. Due to the societal and familial context of her upbringing—pre-Rehabilitation Act America in a military family—Lambert, particularly in her youth, equates power with a masculinist idea of strength.

Even in its mere recounting, the machismo attitude Lambert displays—one that values strength and abhors vulnerability—is off-putting, a testament to her evocative writing and presence on the page. Yet the moments when she feels most powerful because she exerts an inordinate amount of physical, mental, and emotional strength become especially poignant when contextualised within the dominant capitalist culture.

A careful reader will recognise that Lambert’s attitude in insisting to navigate, without help, a society that does not consider—and therefore was not built—for her needs is a symptom of living in a culture where (perceived) ability is currency. In a hyper-individualist America where humanity is reduced to a tokenistic autonomy, isolating independence is valued above community.

Lambert’s narrative triumphs in subtly challenging her own entrenched ideas of power. Illustrated by the shifting dynamics of her relationship with her mother and with her partner Pam, readers experience Lambert’s hard-won self-acceptance of being cared for. Her depiction of care work is nuanced, riddled with guilt and triumph, fear and freedom, and caring for is irrevocably intertwined with taking care of. Throughout this process we see how Lambert comes to understand that, just as “Disability was different from illness,” so too is vulnerability different from weakness.

Despite the specificity of Lambert’s perspective and experience, her writing is bound to resonate with readers of all kinds. Artfully covering topics of independence, the writing process, aging, and familial and romantic relationships, the collection of essays is about much more than the title suggests—her legs.

It is surprising that the collection is titled My Withered Legs. In the essay of the same name (though with the addition of “what is lost” in parenthesis), Lambert details a public obsession with her legs, with editors demanding to hear more details about them. Following this advice would erase the original point of her writing.

Choosing My Withered Legs as the collection’s title serves a dual purpose. It satiates the editor’s and the public’s obsession with her legs, which then drives the point of the titular essay home. I imagine an able-bodied reader—picking up the book because they are infatuated with the idea of reading about Lambert’s legs and struggles with disability—having a rude awakening when they realize they’ve played into the exact issue the author is critiquing.

The challenges Lambert faces in publishing her writing leave questions about what didn’t make it through the editorial filter, i.e. “My Withered Legs (what is lost),” and whether or not her wide appeal is something to be celebrated. In “Crip Humor,” Lambert explains that people using wheelchairs and their community would find the story funny. Explaining the joke makes the essay understandable to a large audience, but it became Lambert’s role to make that kind of understanding possible. If Lambert hadn’t had to cater to an able-bodied audience, how would the essay differ?

Readers can only speculate the answer to that question, and can only imagine exactly what was lost. In the meantime, Lambert’s collection is a perfect read for anyone pondering power—inside or outside the pages.

Kali Herbst Minino is a freelance journalist based in Seattle who works primarily for Seattle Gay News. They use a restaurant job to help fund their freelance journalism habit and love reading about labor movements, feminism, and media studies.

Gabe Tejada is a writer and reader based in Naarm/Melbourne whose work has been published in Archer Magazine and Kill Your Darlings, among others. His greatest achievement thus far is his 800-day Duolingo streak.

"Empowerment comes from ideas."

― Charlene Carruthers

"Your silence will not protect you."

— Tourmaline

"Gender is the poetry each of us makes out of the language we are taught."

— Leila Raven