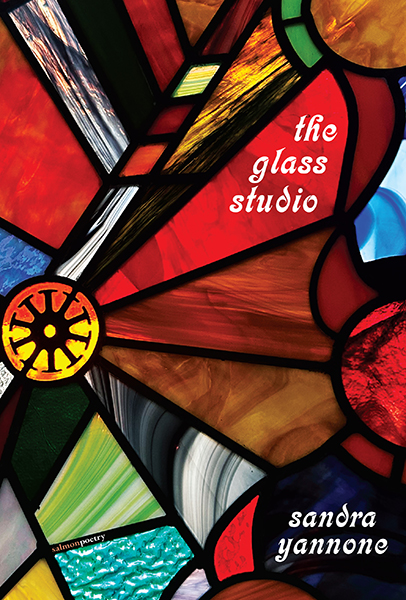

The Glass Studio

Sandra Yannone

Salmon Poetry, 2024, 98 pages

$13.03

Reviewed by Karen Poppy

How does one reckon with a father and with family, and how does one reckon with growth and grief? In The Glass Studio, Sandra Yannone does so expertly, combining the painful, sharp shards and melding them into costly, prismatic beauty. She dedicates this poetry collection in memory of her father and paternal grandmother, two family members whose inexorable influence on Yannone (and her responding tenderness towards them) is palpable.

Within Yannone’s collection, we find family and patriarchal myths pieced together. The myths, like the stained glass, fused and shimmering, are dangerous and alluring in their creation and perpetuation, but an art form of liberation when we act in their dismantling. Dismantling myths is a key component of the quest for love and understanding. On the journey to reach love and understanding, one of the poems, “The Properties of Glass,” explains that “we are not anywhere / a map can call / home. We are not anywhere / a map can comprehend” (76).

To gain wisdom and reach love and understanding for ourselves, we must look back towards home. We must return to our familial origins, which Yannone deftly retraces in The Glass Studio. She writes that like a lover gifted “a petite, stout jar / of tap water and sea glass / worn down / by years / of turbulent waves / and rocks,” we learn about “the things that have cut me open and made me bleed” (9). Time smooths over the shared vulnerabilities and beautifies pain caused by sharpness. Pain becomes stained glass, glistening in waves of words, and loving; imperfect family members roll in the poetic, rocky deep.

The book’s structure maintains the varied patterns and repetitions of stained glass, divided into four parts, with four poems titled “The Glass Studio,” mirroring the book’s title. In the aforementioned poem in the book’s third section, the speaker looks back at her fourteen-year-old self in her father’s stained glass art studio, stuck in time and place, symbolically and in a photograph. Yannone writes of a photograph taken on

“an early morning in my father’s makeshift sweatshop / on the unfinished second floor of my grandparents’ house, / leaning over beige glass squares arranged / in a plaster-poured mold, my Red Sox cap / cocked backwards like a trigger / waiting for release…” (62).

We see the speaker through this photograph, this memory, “cocked backwards like a trigger” (like her Red Sox cap), seemingly frozen at this moment but ready for release.

The speaker looks back, older and wiser, with wisdom informing her of ways the family system poisoned and trapped her. She describes coming of age through her father’s craft and the patriarchy’s myth—rendering splendor and dazzling truth from toxicity. Wisdom allows for a slow, thawing release, not the quick pull of a trigger, in this poem and throughout the collection. Yannone is released from patriarchal myth as she finds release from family myth through retelling her story. In patriarchal myth, the gorgon, with coiled snakes writhing on her head, has such a gruesome appearance that men turn to stone merely by looking at her. The powerful gorgon, once revered as a protectress and representative of women who healed others, becomes fearsome and ugly—and dangerous—within the patriarchy’s story.

For the speaker, the coiled snakes melt in the making of stained glass into seams, bringing together and holding the glass, which appears beautiful in the light but is as brittle as male fragility. Those socialized as female learn at a young age that their power must melt away- that they must pacify and hold everything together. They must make everything beautiful. The speaker also learned this skill from her father in making stained glass:

“my left hand / steadying the burning soldering iron / while I push coiled snakes of lead / into the iron’s hot tip to melt them / into quick silver seams, fusing / those cut glass squares / into translucently beautiful panes / if I hold them up to the light / breaking through the second floor / window” (62). The melting of the gorgon’s coiled snakes is as harmful and poisonous as it is difficult: “I sweat through this labor. / I breathe in the noxious fumes” (62).

Within this toxicity, there is also genuine love and important teaching from the speaker’s father. Yannone transforms her father’s example from destructiveness into healing, sapphic passion. She ultimately transforms what breaks women through her precise and gentle lovemaking:

“I wear no protective mask. My hot pink / lungs slow burn towards death. Hour / after hour, I run my hands like this, iron / and lead, like over the seams of women’s bodies / it will take years for me to touch. / I use the same precision to bring them / full circle, to where they become / translucent. / My father will teach me all this / with squares of cut glass, not ever / saying the word “sex,” without ever / claiming to transfer the knowledge of how / he broke my mother’s body / to create something sacred / akin to a family” (62-63).

This review ends with fitting words from another poem in this collection: “And in response to my longing, / I burn the toast” (68).

Karen Poppy has a debut full-length collection, Diving at the Lip of the Water, published by Beltway Editions (2023), and lauded by the legendary Judy Grahn for its demonstration of “paradox and power.” She has two chapbooks published with Finishing Line Press, and another chapbook published with Homestead Lighthouse Press: Crack Open/Emergency, our own beautiful brutality, and Every Possible Thing.