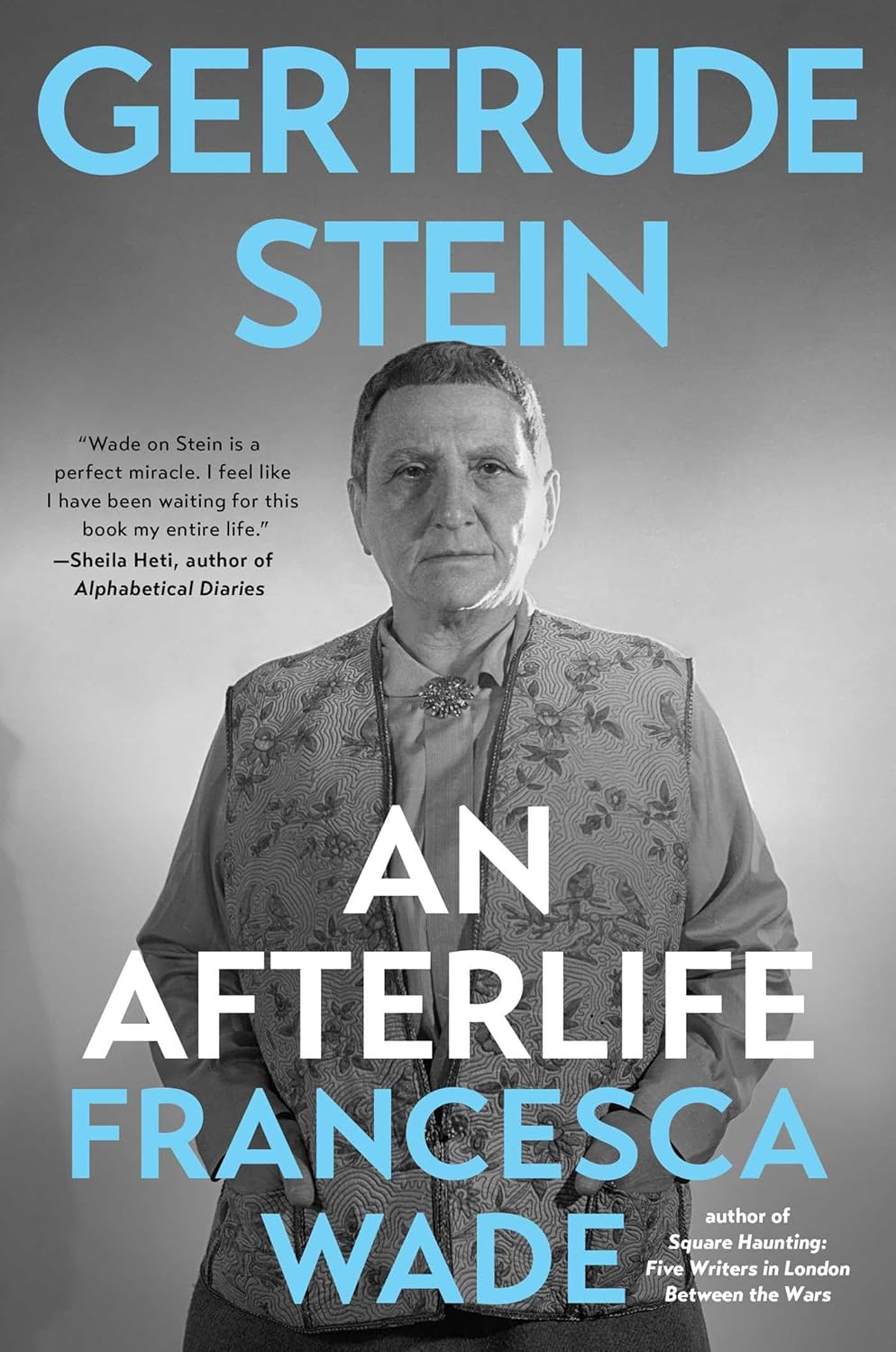

Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife

Francesca Wade

Scribner, 2025, 480 pages

$31.00

Reviewed by Martha Miller

Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife is a book divided into two parts. The first is the life of Gertrude Stein when she came to Paris with her brother Leo, who was interested in art, and the beginnings of her art collection. What follows is twenty-some years of their lives through some of the greatest history of literature and two wars in Paris, as Stein meets and befriends Alice B. Toklas, falls out with Leo, and during World War II hides out with Toklas in a small French town—writing, living, and loving. The second part begins with Stein’s death and Toklas’ efforts to publish Stein’s prolific unpublished writings. Toklas worked with scholars and powers that be at Yale, where Stein’s papers had been donated, for twenty years as she aged and finally died. In an effort to save Stein’s papers, Toklas accidentally sent a scholar not only books, but notebooks containing hers and Stein’s personal lives. Thus Stein and Toklas’ personal life became public. An unpublished book titled Q.E.D. that contained the events of Stein’s first lesbian affair, before she met Toklas, a secret for which Toklas never quite forgave her, was published under another title. It’s hard to reduce Wade’s book, which is so rich in information, into the length of a review. While a great deal of An Afterlife is written in academic passages, in fact, it’s not a difficult read. There’s something about it that compels the reader forward.

When Stein died in 1946, the bulk of her writing was unpublished. Her work, Wade claims, was all her life “spurred by her scientific background” (3). Trained in medicine as a young woman in the US, this influence is clear later on in her writing. Stein asked questions about how perception worked, how words made meaning and embody the essence of people, places, things, and existence. She saw words as living things with physical properties, like materials a painter or sculptor might use to shape something new. Stein did with words what an artist does with paint.

Stein may be called less a writer in the conventional sense than a philosopher of language. As a woman with a wife, I liked the phrase, “My wife my life is my life is my wife,” (105). I admit that before reading Wade’s book, the most I knew about Stein was ‘a rose is a rose is a rose,’ which I discovered was so well known that Toklas had it embroidered on several objects in their home. I knew that Stein was an overweight lesbian who wrote in repetition and was often difficult to read. Her process was sleeping late and writing, and then Toklas typed up the writing the next day. She loved reading mysteries and often read one a day. In later years, during a trip to America, she wanted to meet Dashiell Hammett. One thing I think most know about her is she entertained visitors in her room with walls covered with paintings. The studio gatherings consisted of painters, modernist writers, and their wives. Stein entertained the artists and Toklas the wives. I actually started to wonder if Stein had not been an overweight, openly lesbian female, her writing might have been considered on a level of Joyce, Faulkner, and other experimental writers of the modernist or post-modernist era. The truth was, “Stein always made people uncomfortable” (375).

Stein’s second book, The Making of Americans was completed in 1912 when Stein was 38. It was a reparative classic immigrant narrative. New people make new existences out of old lives. Stein did not make a profit from her writing even though the women self-published five titles under the trade name of The Plain Editions between 1930 and 1933. She and Toklas financed the books by selling a Picasso. Whenever money was tight, they looked toward the many paintings in their studio. Nevertheless, Stein soon started to make a little money from The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas published in 1932, and an opera, Four Saints in Three Acts, for which she wrote the words and Vergil Thompson wrote the music. One very interesting part of Stein and Toklas’ life was World War II when, as two aging Jewish women, they left Paris and stayed in the country. Paris was invaded and eventually so was the small town where they hid. But they survived to return to Paris.

Gertrude Stein died on July 27, 1946 of uterine cancer, leaving Alice B. Toklas a widow for the next twenty years, with four hundred dollars a month and a mission. All property, including stocks, bonds, $82,000 cash, royalties, and the high-priced paintings from the studio, belonged to Stein’s nephew, whom neither woman was close to. Four hundred dollars a month in 1946 may have been adequate for living expenses, but as the next twenty years passed, the compensation paid for less and less. As time passed, Toklas frequently borrowed money from friends just to get by. After Stein’s death, only two books made money. The first was Q.E.D., the second was We Eat: A Cook Book, by Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein, which Stein wrote most of. These royalties went to Stein’s nephew.

Scholars who worked with Stein’s writing discovered that it changed over the years; in the beginning she used syntax to explore the inner process of emotions, and later she used language from literary conventions to explore her own feelings. With Q.E.D., Toklas pondered the final success of Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt which after several rejections she finally published in pulp. Q.E.D. was published and a success. Toklas never abandoned her mission to get the rest of Stein’s writing published. Thanks to her, more of Stein’s writing was published after her death than before.

While the beginning of the book was an exciting love story, this later part was sad, as Toklas’ health went downhill. She died March 7, 1967 and was buried in the same grave as Gertrude Stein. Here the story is well written and interesting, and is also heartbreaking, for as Toklas became old and ill, much of her life was told from the point of view of scholars and publishers who worked with Toklas and watched her struggle.

Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife is full of pictures and illustrations that support the story. I found this a well-written and easy-to-read book about a well-known modernist literary figure and a better-known early-twentieth-century lesbian couple. Their devotion to art and literature as well as to each other is remarkable.

Martha Miller is a retired English professor and a Midwestern writer whose books include fiction, creative nonfiction, anthologies, and mysteries. Her nine books were published by traditional, but small, women’s presses. She’s published several reviews, articles, and short stories and won several academic and literary awards. Her website is https://www.marthamiller.net/. Her Wikipedia page is https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martha_Miller_(author).