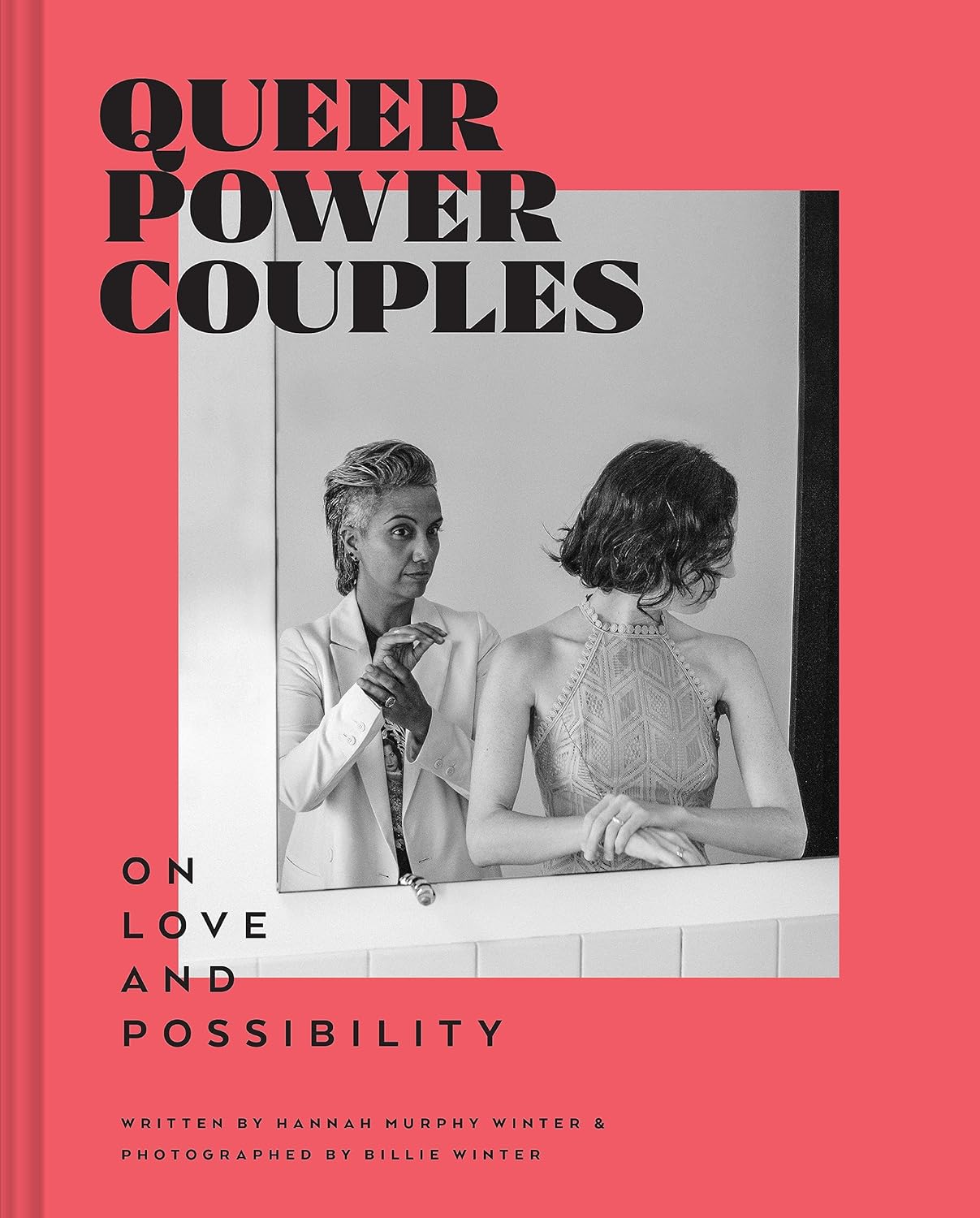

Queer Power Couples: On Love and Possibility

Hannah Murphy Winter, photographed by Billie Winter

Chronicle Books, 2024, 248 pages

$29.95

Reviewed by Bailey Hosfelt

Journalist Hannah Murphy Winter and photographer Billie Winter explore the power of queer love and the politics of visibility in a collection of in-depth interviews and intimate photography in their new book, Queer Power Couples: On Love and Possibility. A collaborative project by the authors who are also wives, this release is both a visually beautiful art book and a thought-provoking read. It offers readers a glimpse into the rich lives of fourteen queer couples, spotlighting their thriving relationships, varied forms of creative expression, and personal and professional achievements.

Divided into three sections, the book interviews queer power couples, which the authors define as couples who are out, coupled, and able to influence mainstream culture across diverse industries and from different embodied perspectives. The book features famous partnerships such as Mike Hadreas and Alan Wyffels of Perfume Genius, Jenna Gribbon (artist) and Mackenzie Scott (musician known as Torres), Roxane Gay (author) and Debbie Millman (designer), and comic artists Molly Knox Ostertag and ND Stevenson, among others. The book also includes partners with successful careers in other fields, such as fine-dining chefs Samantha Beaird and Aisha Ibrahim, academic scholars Marilee Lindemann and Martha Nell Smith, and influential scientists Barbara Belmont and Rochelle “Shelley” Diamond.

Whereas Murphy Winter’s journalistic work often covers queer pain—namely, the laws, legislatures, and political administrations trying to erase queer people—Queer Power Couples intentionally deviates by centering queer joy and affirmation. As the authors write in the introduction, queer people must often locate queerness in small moments or nuances to find proof that they’re not alone, a process that involves “sifting for scraps” (10). In contrast, Queer Power Couples’ presentation of queerness is neither ephemeral nor implied. Instead, it offers an authentic showcase of queer individuals who are out and proud, spanning various ages, demographics, and lived experiences. By highlighting queer lives and amplifying their visibility, this book and its interview subjects make a crucial contribution to broader LGBTQ+ representation, especially for younger queer readers.

Queer Power Couples certainly spotlights its interviewees’ big wins, such as publishing a book, going on tour, and producing a television series. However, the book’s strengths ultimately lie in its emphasis on the joys in the smaller, everyday moments couples experience together: reading on the couch, walking a dog, or preparing a meal. Through these depictions, the authors celebrate the experiences of building and maintaining a life together, including its mundanities—something queer people often fear will forever remain out of reach.

In each interview, the authors asked couples the same question: Who was the first person you recognized as queer? Despite the same query posed to every couple, each conversation was unique. Insightful reflections emerged on how queerness intersects with other identities—such as female, trans, immigrant, Black, Muslim, Christian, Southerner, and parent—and how interview subjects navigated these aspects of themselves, both in times of conflict and harmony.

Murphy Winter’s journalistic chops draw out stimulating meditations from the interview subjects on what it means to step outside the confines of heteronormativity. Winter’s photography (in both black and white and color) provides tender insight into the couples’ lives and loves. With full-page spreads dedicated to both words and photography, and pages that intersperse or alternate between the two, Queer Power Couples gives equal weight to the visual and written, allowing each medium to shine and interlace with the other.

In addition to Winter’s photography, the work includes self-portraits taken by couples and photos partners took of each other. These provide the work with greater intimacy and highlight the relationship between seeing and being seen. Much like lesbian photographers Joan E. Biren (JEB) and Donna Gottschalk, Winter captures couples’ intimacy and connection by photographing them in physical locations that are part of the world they have built together, establishing increased authenticity in her images.

As a quote from Dr. Ilan Meyer, a researcher at UCLA’s Williams Institute, emphasizes early in the book, “A happy gay couple is, in the context of history, a very revolutionary idea” (21). Queer Power Couples celebrates queer life and love, introducing readers to “a catalog of trails that have already been carved out by queer people who are changing the world in their own way, not in spite of their queerness, but at least, in part, because of it” (246). Queer Power Couples is a resonant read, offering queer readers “more maps, torches, and possible selves” (246), just as its authors hoped it would.

Bailey Hosfelt is a lesbian writer. She recently graduated with a master’s degree in gender and women’s studies from UW–Madison, where she wrote a thesis on Dyke TV and queer activist infrastructure. Previously, Bailey lived in Brooklyn, New York and worked as a journalist for local newspapers. Bailey lives in Chicago with her partner and their two cats, Hilma and Lieutenant Governor.