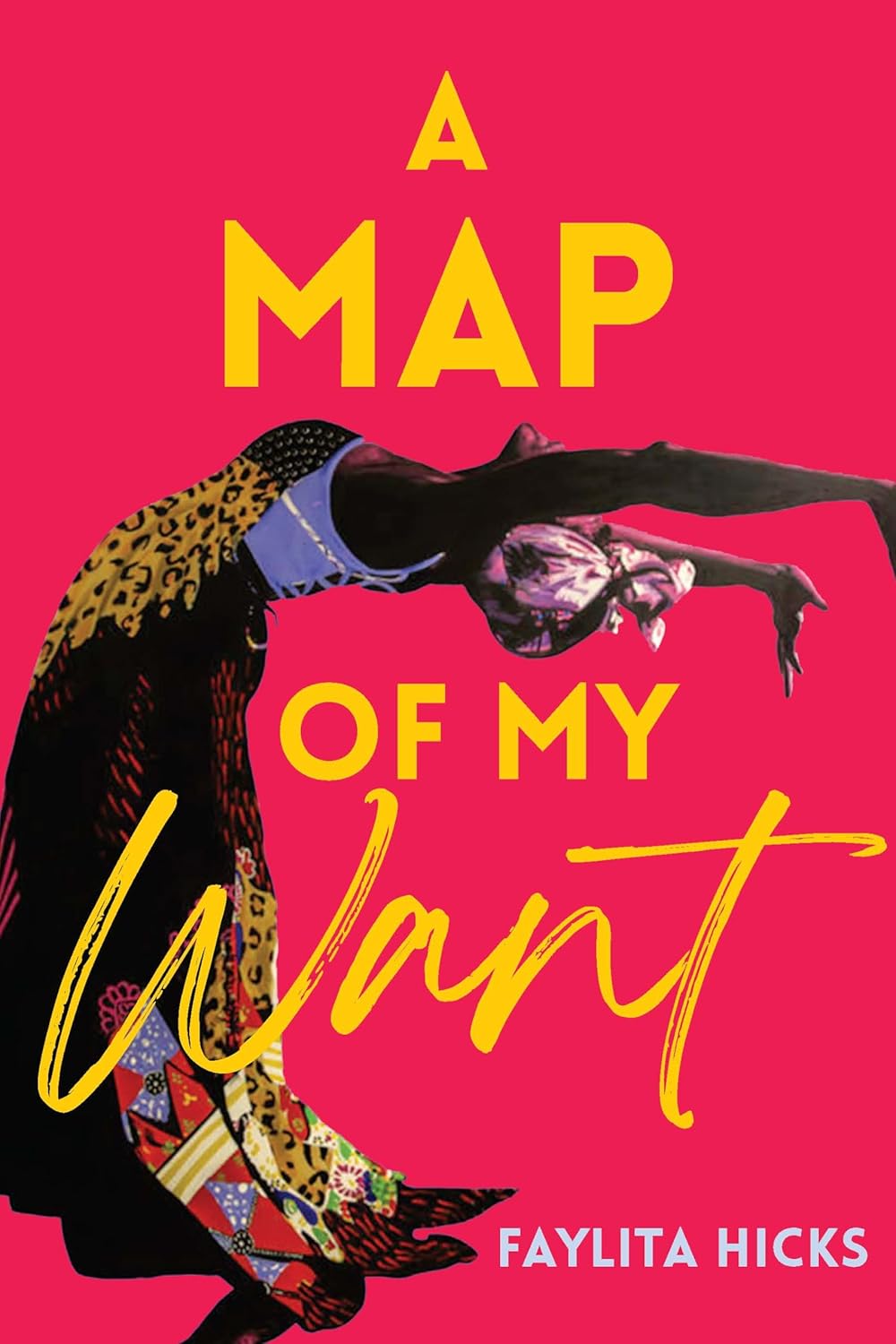

A Map of My Want

Faylita Hicks

Haymarket Books, 2024, 94 pages

$17.00

Reviewed by Dot Persica

During my very first very long lesbian relationship, I gifted my then-girlfriend a copy of The Essential June Jordan. In it, I wrote something along the lines of “this book is mine which means it’s yours which means it’s ours.” This year, I got it back neatly packed in a big cardboard ramen box with (some of) my clothes, my old DS, and some other books. Which means it is now mine alone. As is my copy of A Map of My Want, by Faylita Hicks.

“I blinked and we were in love—

then out of love—

then child-shaped again—then not.

Then both of us alone. Together.

The both of us crying into the empty

of our kitchen sinks.

Jesus—how did we

get here, again?”

(Hicks, “BONFIRE BRIDES,” 29).

June Jordan’s work first taught me that poetry could be something else entirely, beyond rhymes and form, that the idea that one might have to sacrifice content for form is entirely false. June Jordan taught me to see poetry as a weapon.

Reading Faylita Hicks, I held June Jordan, Audre Lorde, Nikki Giovanni, and Emily Dickinson close, as tools to better comprehend what I was interacting with. Lorde and Dickinson are quoted in the book, along with a variety of other writers—Jordan and Giovanni are voices I heard echoing through some of the pages even without them being named. It is their irreverence that I found again in Hicks’ work.

Readers are immediately pulled into Hicks’ world: there is no time for pleasantries, the urgency of Hicks’ voice and the vivid descriptions of images, smells, textures, and specific scenarios create an inescapable sensory trip from the very start. The book is divided in four sections: ALCHEMY, LIFE, LIBERTY, and THE PURSUIT. The omnipresence of the erotic is palpable throughout the book, with the erotic being a natural phenomenon:

“Staring out into this abyss of bush I counted

millions of solar flares, each of them fingering

the ultraviolet of evening, a tinted mimosa

pressing its silk mouth to my swollen knees”

(Hicks, “CHIRON’S BEACH,” 9).

Hicks writes unabashedly about sex and gender, explicit without shame, “What if I was heavy between the legs? What would it feel like to hang my body from a machine—to feel the trickle of time between my skin and shift?” (Hicks, “STEEL HORSES,” 5).

“Who I am now—a kind of boi traveling south//southwest: as far as the stars will

take me

into the land coughing up all of my names, the skin of the road warm (...)”

(Hicks, “ON BECOMING A BRIDGE FOR THE BINARY,” 6).

Parallels are drawn between nature and the body, where one is a metaphor for the other, because they are ultimately the same; borders, frontiers, jails: attempts to contain a body that is meant to be free. Similarly, life and death are also companions who give and take from each other.

Natural disasters are very present in this collection, since Hicks is from California and central Texas, and frequently draws from their experience. Storms and fires are both metaphor and reality, both political and personal—one of the biggest manifestations of the damage done by capitalism, and especially interesting because they don’t discriminate. While the most exploited countries and populations are the ones paying the price of Western climate terrorism, eventually these disasters will catch up with their perpetrators and not even the richest among us will be spared.

Protest in all forms is also an all-encompassing theme, and on these pages the names of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Sandra Bland appear, sparking deeper analyses about America’s constant attempts to disappear Black life, be it by murder, imprisonment, or both. Hicks writes about their life during and after their captivity in the Hays County Jail, and the mental toll of imprisonment.

“For weeks, I forget what the sun felt like.

I forget I was once loved. I forget affection”

(Hicks, “RELEASE||RELEASE,” 58).

One truly cannot imagine what it means to be imprisoned in America if one has not lived it, and Hicks’ courageous voice forces readers to look right when they would rather close their eyes. It is necessary to see these evils if we are to eradicate them.

Hicks’ work is furiously loving, filled to the brim with hope for their communities, their comrades, their friends, their loved ones, love of their latinidad, love for revolution.

“my city is a river

of college students destined to be

swallowed by the rural expanse

of the Guadalupe.

En protesta, we comrades float

outside of the federal building,

—the county jail where I was buried—

En la lucha! against

the waves of the recently shipped,

the waves of the soon to be drowned,

and the waves of white faces swimming

happily in and out of the front doors”

(Hicks, “DO NOT CALL US BY OUR DEAD NAMES: A DOCUPOEM,” 60).

Hicks unites nature, sex, protest, race, gender, justice, and remembrance in this collection, which will speak to anyone who feels strongly about freedom in its many definitions.

Dot Persica (any pronouns) is a lesbian performer born in Naples, Italy. They are a classically trained soprano with some dance training; they have experience directing opera, helping out on film sets, and doing stand-up. They are a cofounder of the italian lesbian+ collective STRASAFFICA* with which they have organized community events, raised funds, published zines and created beautiful bonds. They also write poetry, like all lesbians.